The #ISIRC2019 conference in Glasgow created an outstanding opportunity to take stock of the landscape of Social Innovation scholarship, practice and policy.

September started with the 11th edition of the International Social Innovation Research Conference (#ISIRC2019) in Glasgow. The wide variety of disciplines represented in the community of scholars, researchers and practitioners at ISIRC is overlapping with two research networks. The Research Network for Social Enterprise (EMES) converges around the “SE” concepts: social enterprise, social entrepreneurship, social economy, solidarity economy and social innovation. The International Society for Third-Sector Research (ISTR) is organised around the study of civil society, philanthropy and the nonprofit sector.

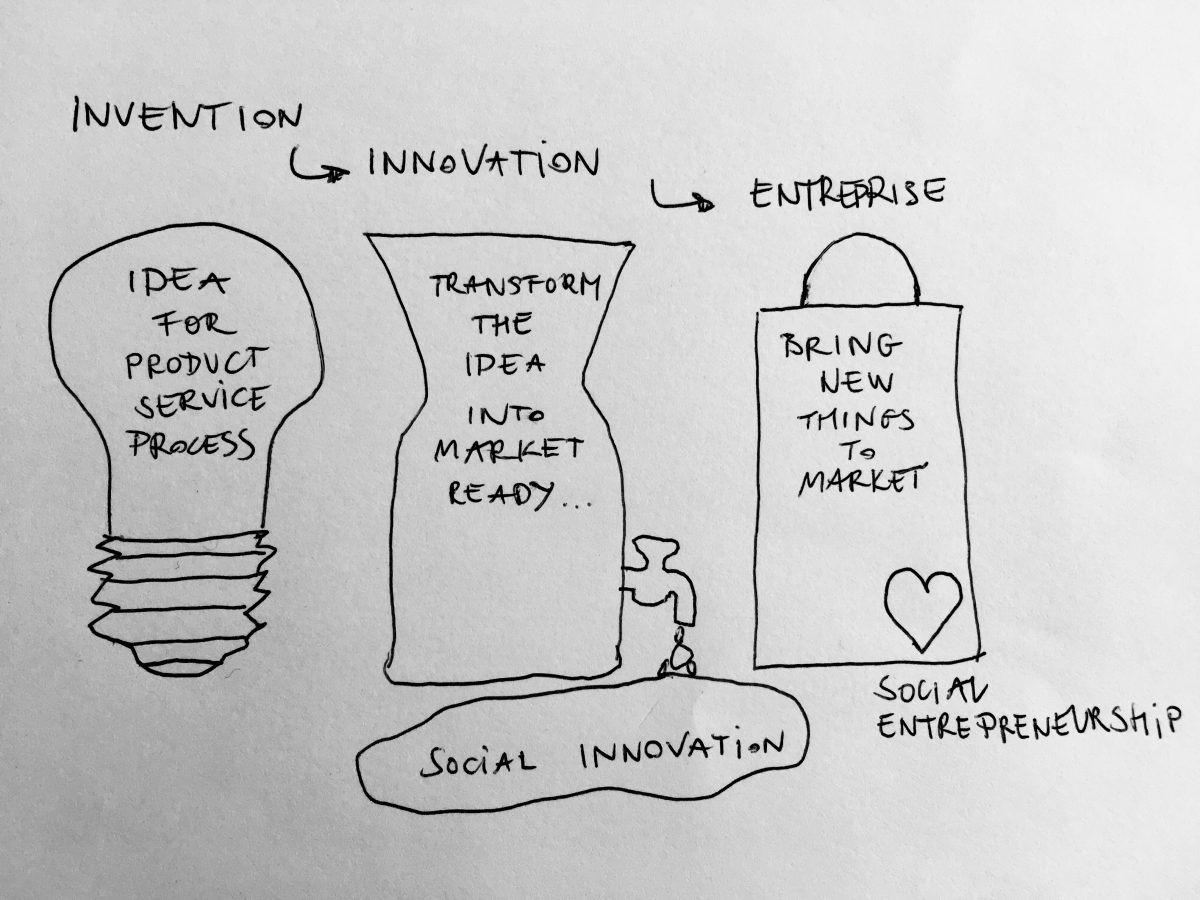

The ISIRC community being very mixed, the locus is on how social innovations and entrepreneurs change society for the better. This change needs a transformation of our social relations to make the world a habitable place – less prone to injustices, inequalities, extinction. Social innovation can take varied – and most often hybrid – formats between the state, the market and the community to best combine public, social and commercial objectives. The event brought together a myriad of research fields around sustainability transitions, transformative social innovation building on economic sociology, public administration, business studies. Dominated by a rather critical and constructive methodological approach which is well aware of its self-referentiality (our own role in changing the world), the whole community develops its self-awareness of our own normative standpoints and its capability to see through the ideologies behind our positions.

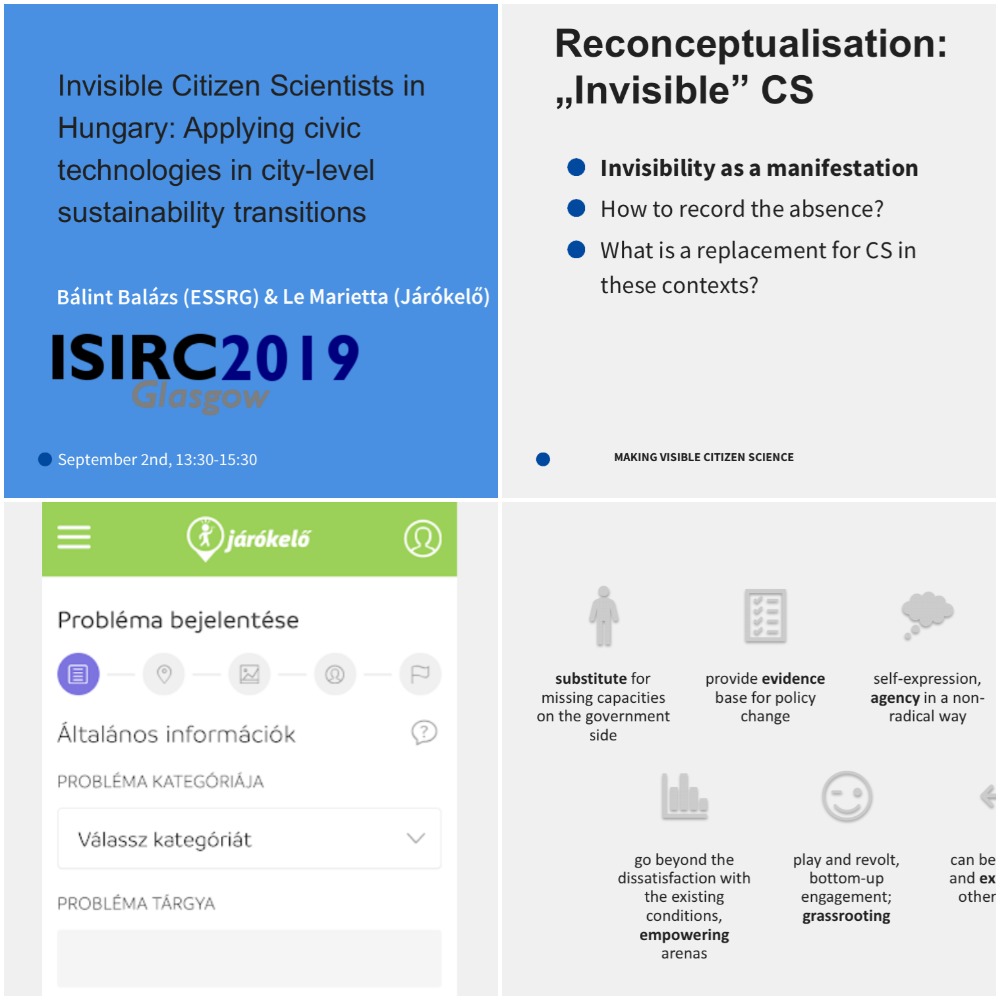

My presentation picked up the socially innovative aspects and potentials of citizen science, especially in places where such citizen science practice is missing, invisible or just emerging. In the session several other examples of digital social innovation platforms were discussed: hackAIR, SavingFood, Coolcrowd.

On the first day, the plenary talk by Simon Teasdale (Professor of Public Policy and Organisations at the Glasgow Caledonian University) started from one key question: what would the world look like if social innovations all were successful. He presented social innovation through the lense of the real utopia, a concept advocated by Erik O. Wright. He presented results of a critical discourse analysis of the contents of homepages of two social innovation intermediaries, SIX and Ashoka and compared their ecosystems, networks, fields to show how their transformation logics lead to ruptural, interstitial, symbiotic transformation.

Our own Prof Simon Teasdale giving a plenary session at #ISIRC2019 @isirc2019 on utopias of social innovation @YunusCentreGCU #socialinnovation pic.twitter.com/UJbbQ9gJ1s

— Rachel Baker (@Rachmb25) September 2, 2019

The second-day keynote by Stephen Osborne, the Chair of Public Management and Director of the Centre for Service Excellence and ex-vice Dean at the University of Edinburgh Business School looked at the role of the third sector in public services delivery. He discussed the role of co-production and co-creation of value in public service delivery and design drawing on the results of the Co-Val EU H2020 project.

The great @StephenOsborne1 at #isirc2019 on public service innovation. Very resonant. “Innovation isn’t change. We have a word for change. It’s called change…….Public policy should be about what values we hold and making them extant. Not just about the design process.” pic.twitter.com/OhY1EnmRVf

— The Skill Mill (@The_Skill_Mill) September 3, 2019

In the afternoon Jürgen Howaldt, the Chairman of the European School of Social Innovation, Scientific Coordinator of the SI-DRIVE EU FP7 project and the Director of Social Research Centre at TU Dortmund University and Professor at the Faculty of Economics outlined a systemic perspective on Social Innovation research and discourse. He emphasised the role of designing and maintaining infrastructures and resources that help flourish social innovation and create impact. He concluded that whereas there is increasing acknowledgement and promotion of social innovation in the EU 2020 strategy, in many instances, we do not find it at the core components of innovation policy.

Bird’s eye-view of social innovation research & discourse by Prof Jurgen Howaldt at #isirc2019: from innovation studies, transition research and social imaginaries, to transformative innovation manifesto and policy https://t.co/ohItPR4hpv pic.twitter.com/74wgMExNkc

— Flor Avelino (@FlorAvelino) September 3, 2019

The third-day keynote by Helen Haugh, Research Director for the Centre for Social Innovation at the Cambridge Judge Business School discussed social (and community) entrepreneurship and social innovation from the viewpoint of common good theory based on her extensive experience on community-led asset-based regeneration in rural communities.

Excited to have a chapter (mostly thanks to Helen Haugh from Cambridge Uni) in this new research agenda book on social entrepreneurship #SocEnt https://t.co/PUroK41ynd

— Andy Brady (@3dSectorFutures) September 4, 2019

Helen Haugh emphasised the role of contextual conditions that advance human well-being. Social enterprises create hybrid strategies to contribute to, give, stake and take the common good. Common good giving (or generalised reciprocation) is when you add to the common good without expecting direct returns. Taking common good is non-reciprocation, and it clearly diminishes common good. Moreover, she differentiated tolerated reciprocation vs. negative reciprocation. For future research, she suggests to explore measurements and indicators of common good giving and taking, also to extract the creation mechanisms and diffusion models for common good giving. Our role as researchers is to find passion in our research, she advised, and be reflective.

RT @FlorAvelino: What is it all for? Dr. Helen Haugh unpacking notions of “common good” & “(non-)reciprocation” in relation to #socialenterprise & #socialinnovation. “As researchers we’re supposed to be impartial… Well, the hell with that”. #isirc2019 pic.twitter.com/08915dezYl

— Social Innovation 2030 (@inno_2030) September 4, 2019

The final plenary by Eleanor Shaw, an engaged entrepreneurship scholar, the Vice Dean of Strathclyde Business School and the designer of UK’s first empirical study of social entrepreneurs ask where social innovation is going.

Prof Eleanor Shaw final plenary at @isirc2019 – social innovation looking back to the 90s pic.twitter.com/UFT5vBFeam

— Sharon Zivkovic (@SharonZivkovic) September 4, 2019

She gave a concluding overview of the future of social innovation research, policy and practice. Her work focusses on the impact of financial and non-financial capitals in the creation and growth of entrepreneurial ventures, particularly social enterprises. From this angle, it is clear that the future of social innovation is uncertain; it can very well maintain its political acknowledgement as well as dissolve in replicating itself. Therefore an essential focus needs to be on the quality of learning interventions that support (social) entrepreneurial organisations to create shared value.

See more highlights from our TRANSIT H2020 project coordinator, Flor Avelino below.